Why I think “Backgrounds” Are at Play in 1 Timothy 2

Hint: It's not because I'm a liberal.

Last time I explored when to appeal to Bible backgrounds when interpreting Scripture. Here I’ll build on that content and address how backgrounds can help us understand Paul’s instructions about women in 1 Timothy 2.

I’ll begin by adding one thing I left unmentioned last time that’s worth stating:

Anyone using a dictionary is relying on background info.

All the people who use a lexicon like the Koine Greek/English dictionary to understand what words meant in their original contexts are drawing on backgrounds. Take the words agape, storge, eros. Ever heard that the earliest Christians used these words to differentiate between kinds of love—in this case, sacrificial, parental, and erotic? That knowledge relies on backgrounds. The very definitions of words from the ancient world (or any world, really) rely on backgrounds, on knowing the original contexts. So, if I go to my lexicon and ask it about the word “childbearing” in 1 Timothy 2:15, I find this:

τεκνογονία, ας, ἡ (s. prec. entry; Hippocr., Ep. 17, 21; Aristot., HA 7, 1, 8, 582a, 28; Stoic. III 158, 5; Galen: CMG V/9, 1 p. 27, 12; Cat. Cod. Astr. IX/1 p. 181, 17)

the bearing of children 1 Ti 2:15 (RFalconer, JBL 60, ’41, 375–79; SPorter, JSNT 49, ’93, 87–102; NDemand, Birth, Death, and Motherhood in Classical Greece ’94).[1]

Look at that first line and you will see two abbreviations: “Hippocr.” and “Aristot.” Hippocrates and Aristotle. The English translation of teknogonia as “the bearing of children,” relies on the word’s usage in Hippocrates’s De Officina Medici, Part 17 and Aristotle’s in Historia Animalium (History of Animals), both fourth-century BC sources. I took this entry right out of “BADG,” a standard Greek/English dictionary for Bible scholars. But in fact, every dictionary relies on background info to help us know what words mean. Anyone reading the Bible in anything other than its original autographs requires “backgrounds” to help us with definitions.

Backgrounds help us understand Paul when he talks about women in 1 Timothy.

When it comes to Paul’s meaning when he talks about women in the church in his first epistle to Timothy, here are the two camps:

Local problem: Paul as addressing a problem in a limited context when he says he is restricting women’s (or wives’) teaching/authentain a man (or husband) (1 Tim. 2:12).

Timeless ideal: Paul is saying women are to use their spiritual gifts of teaching in the church only with biological children and other women, and this practice is timeless. That’s because Paul’s rationale for doing so is “for Adam was first.” Paul is appealing to the ideal pre-fall state. So he must be laying out a principle that “only male teachers in the church” is God’s ideal for all time, rooted in the pre-fall, perfect state.

Some say the two camps are egalitarian (local problem) and complementarian (timeless). Not true. The difference between egalitarians and complementarians is, at its core, about hierarchy, not belief in using Bible backgrounds.

Now then, did you know “Adam was first” has not always been the rationale of the church for limiting women’s teaching? As Edwards and Mathews point out in 40 Questions about Women in the Church (Kregel Academic, 204), “For centuries, hierarch scholars understood verse 13 to mean that women were not to teach men because they were intellectually inferior to men.” The authors cite William Witt, who wrote Icons of Christ, as saying, “Women were considered less rational, more gullible, and more susceptible to temptation, and thus were restricted not only from church office, but from any position of authority over any men in any sphere whatsoever.”

Edwards and Mathews go on to say of women, “Their subordinate rank to men came about because they were defective in their personhood. Today’s hierarchs have largely abandoned inferiority as a reason for women’s subordination, acknowledging that women are no more gullible or less intelligent than men. Instead, they point to 1 Timothy 2:13 and Genesis 2—creation order—to reach the same conclusion. They now say that because Paul grounded his argument in creation, a universal truth, he was speaking of all women in a universal sense when he told Timothy that they could not teach men.”

Did you catch that? The argument shifted from the “Eve was deceived” part of the passage to “Adam was first” when we figured out that women collectively are not, as it turns out, more easily deceived than men collectively. (This reminds me of the world I inhabited before the Title IX landmark federal civil rights law in the US. People told us girls we could not play team sports on the competitive level because our bodies were not made for sports like men’s bodies are. Once the law required our school to add women’s sports, I played on the school’s first women’s varsity soccer team. Today, women’s sports are a $2.3 billion industry. See here, here, and here.)

Backgrounds help us see why the idea that “women are second because God designed the theological world as men first” is contrary both to Paul’s logic and his practice (see Romans 16). Here’s how:

Appeal to backgrounds when doing so allows us to see authors as personalizing their teaching rather than contradicting themselves. Three chapters after Paul says “she will be saved through childbearing” (1 Tim. 3:15) he goes on to add that he wants younger women to marry and have children (5:14). But that differs drastically from what he told the Corinthians: “To the unmarried and widows I say that it is best for them to remain as I am” (1 Cor. 7:8).

We have three options for why he gave two opposite pieces of advice: (1) Paul contradicts himself; (2) Paul changed his views on marriage during the years (five or so?) that passed between the two letters; (3) Paul is addressing a cultural situation in Ephesus (asceticism) that differs from the one in Corinth (sexual immorality). So he writes different advice to different audiences (church in Corinth; Timothy in Ephesus) in differing contexts. Seeing a cultural context best solves the problem of seemingly contradictory advice.

Appeal to backgrounds when doing so helps us fit small parts into a larger whole.

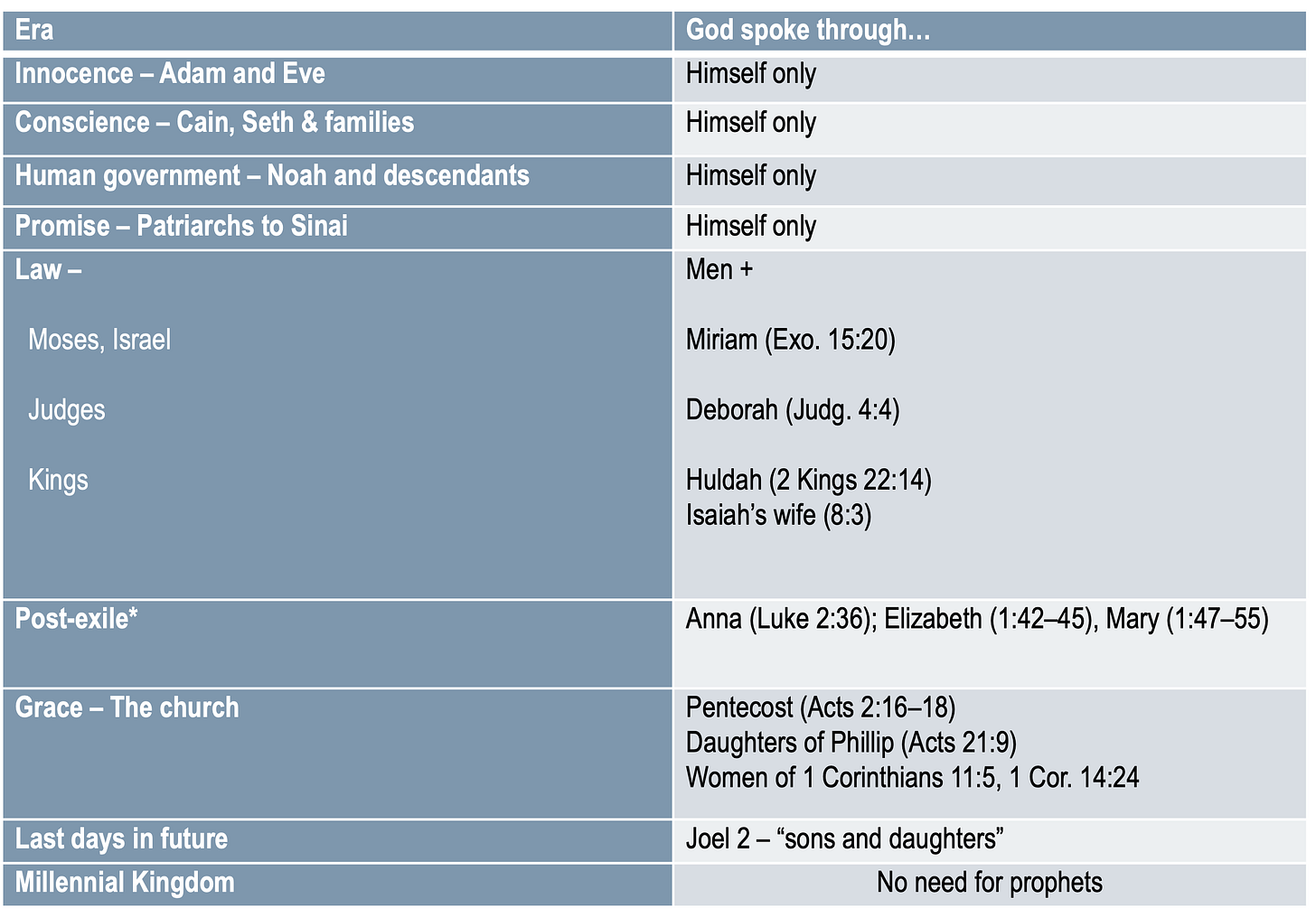

Throughout salvation history the Holy Spirit blessed women with prophetic speech. On the day of Pentecost women’s public proclamation from God was a sign not of male failure but rather the presence of the Holy Spirit. If we are to read 1 Timothy 2 saying “Adam was first” as a “for all time prohibition grounded in creation,” how are we to synthesize such an interpretation with numerous other scriptures that tell us God raised up women to speak for him publicly?

Appeal to backgrounds when doing so helps interpreters be consistent with word usage and grammar. Paul writes “she will be saved through childbearing” (1 Tim 2:15). If we say (as some do) that Paul uses “saved” here to mean “sanctified” or “kept from obscurity,” we require a meaning for “saved” that’s inconsistent with other Pauline use. Here are the four times outside of 1 Timothy 2 in which Paul uses the same form of “saved” (I’m using the NET Bible):

Rom. 9:27 – “And Isaiah cries out on behalf of Israel, ‘Though the number of the children of Israel are as the sand of the sea, only the remnant will be saved.’”

Rom. 10:13 – “For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.”

Rom. 11:26 – “And so all Israel will be saved, as it is written: ‘The Deliverer will come out of Zion; he will remove ungodliness from Jacob.’”

1 Co. 3:15 – “If someone’s work is burned up, he will suffer loss. He himself will be saved, but only as through fire.”

Paul does not use “shall be saved” to mean “sanctified through mothering,” as if bearing children were the only legitimate outlet for women’s teaching. Some say that is Paul’s meaning here, but in doing so they create a new Pauline meaning for “shall be saved.”

Instead, all of Paul’s usages in these references refer to eternal salvation. That’s why some see “the childbearing” as a reference to Jesus’s birth and Paul referencing eternal salvation through Jesus. here. That is a seriously legit interpretation.

Yet the singular-to-plural flip from the quote (“she will be saved if they…”) could also indicate Paul is using quoted material, which he often does in the Pastoral Epistles. The she/they combo constitutes improper grammar in both Koine Greek and English—unless we consider the option that Paul is taking a popular quote and giving it his own spin. The next verse says, “This is a faithful saying,” so his phrase could refer either to what came before or after the note. It could refer to a local saying he is modifying (“she will be saved” if they…) rather than referring to a saying that follows: “If someone desires to be an elder they desire a good thing” (1 Tim. 3:1).

So, if we pull in backgrounds, because Artemis of the Ephesians was the goddess of midwifery, it’s legit to see the pastoral Paul as addressing the number-one cause of death for women—childbirth—and giving a consolation. People using magic in Ephesus learned Jesus was better by seeing the non-normative miracle of people healed through touching handkerchiefs and aprons Paul touched (Acts 19:12). Perhaps those appealing to Artemis for delivery in birth learned Jesus was better by seeing the non-normative miracle of women saved, or surviving, childbirth after renouncing Artemis. We do see “saved” from literal death as a meaning for “saved” in the Gospels.

Regardless of which way we go with in understanding “saved,” consistent word use steers us away from seeing Paul as talking about baby-making as the one legit avenue for women to use their teaching gifts. Telling a woman to re-direct use of her spiritual gift of teaching away from the Body of Christ and toward her biological (usually nuclear family) sounds, ironically, like capitulating to contemporary (my husband suggested I add here “male hierarchical”) Western culture.

Appeal to backgrounds if the writer himself has already appealed to local specifics (backgrounds) in the same passage. In 1 Timothy 2, before addressing women [or wives], Paul addresses men [or husbands]: “So I want the men in every place to pray, lifting up holy hands without anger or dispute” (1 Tim. 2:8). Does your church require men to raise hands when they pray? Mine neither. I’ve often heard it taught that raising hands was a practice done in Paul’s day (limited to a specific context).

Many interpret Paul’s instruction about males raising hands as addressing a local issue. This instruction appears seven verses before his instruction about females. So it’s consistent to consider the possibility of a limited application for what follows if we have already accepted a limited application for what precedes the part about females.

My point: It is inconsistent to say that the instruction for men is for men in Ephesus in Timothy’s care, but the instruction about women is for all time.

Yet many see a key difference between the two. Because in the case of the latter, Paul appeals to something timeless: Adam was first, and he was first in the ideal state rather than as part of the fall. Thus, they conclude, the principle of “Adam first” is God’s ideal. Which brings me to the next point:

Appeal to backgrounds when doing so facilitates consistent handling of literature. I have asked numerous groups, “If I say, ‘Adam was formed first,’ would you say I’m making a historical statement or stating a principle?” Unanimously the answer has been “statement, not principle.” A simple understanding of how narrative works says that “Adam was formed first” is an observation drawn from the Genesis story. Yet some interpret “Adam was first” as a principle extrapolated to all men—men first. Thus, when people read the Genesis account with a male-priority understanding in mind, they see male-over-female hierarchy. Hierarchy is not the point of the Genesis narrative unless one reads hierarchy back into interpretations of Genesis based on how they are interpreting the New Testament.

Yet, it’s a more consistent use of literature to understand the Genesis creation story referenced in Paul’s argument as a corrective to the audience’s theological origin story. That is how stories generally work. We want to avoid making a principles from a story. Do we say David took five stones to conquer the enemy so the principle of five-ness says we too need five weapons when we take on the enemy? That’s not how narrative works.

We know from the Book of Acts and from history that the Ephesians were huge fans of Artemis. And in her creation story, she is the twin of Apollo. And she is first. Protos. In his Description of Greece, Pausanias, a Greek traveler and writer from the second century AD, mentions a statue and altar within the Temple of Artemis. Of it he says, “as you enter the building…there is a stone wall above the altar of Artemis called Goddess of the First Throne.”[2] Protothronos.

Paul reminds Timothy of the Genesis story in which “actually the man was first and the woman was even deceived.” That is not to say all men are preeminent over women. Or that women are more easily deceived. We could cite a different part of the same story to argue against people who say men are preeminent—by noting that the only thing needed for creation to be “very good” was the presence of woman. But we don’t do that. Also, we could argue that the man, not being deceived, full-on sinned. But we don’t. Rather, humanity is the pinnacle of God’s creation, bearing His image. He made us to rule and multiply to fill the earth with worshipers. But we sinned. All sinned. We’re all rebels.

Acts 19 gives a lot of context for what was happening in Ephesus when Paul had to leave town. We initially understand Artemis’s hold on the city less from history or archaeology’s “cultural” info than from Paul’s experience in Ephesus as recorded by Luke (Acts 19). (Sometimes the Bible itself gives us the background.) Artemis has such a hold on Ephesus that Paul had to end his years-long term in the city and leave ahead of schedule because his gospel work had a profound effect on the economics of those who crafted statues of the goddess for sale. We can use archaeology and inscriptions and coins to tell us more about Artemis’s cult, but the suggestion that Artemis was deeply influential comes from the New Testament itself.

All these together point to the need to look to background info to help us properly understand 1 Timothy 2. And if we do assume a specific cultural situation in view in Paul’s instruction, our doing so also solves a few additional textual issues:

We can reconcile contradictory advice given to the church in Corinth vs. Timothy in Ephesus.

We can reconcile teaching about women in 1 Timothy 2 with the whole canon of Scripture that has women in numerous settings filled with the Spirit and proclaiming the word publicly with men present.

We can return to seeing narrative as narrative rather than narrative as principle. In doing so, we can view creation order as part of a story in Genesis that points to male and female as needing each other rather than as God creating male-over-female hierarchy.

We can read the creation story as both male and female equally responsible for sin, as Genesis presents the story, rather than as Eve being as more responsible (1 Tim 2) or Adam being more responsible (Rom 5).

We can eliminate the question of how old a male must be when he must stop listening to women saying true things.

We can once again encourage men to learn biblical truth from their spiritually gifted and equipped sisters in Christ.

We can eliminate the need to see the text as saying all women are more easily deceived than men.

We can see that all humans who are given spiritual gifts use them for the good of the body of Christ, rather than prioritizing the biological family over the spiritual one.

We can stop using someone’s interpretation of 1 Timothy 2 as a litmus test for whether they are egalitarian or complementarian. It is such a test only for how someone uses backgrounds.

People really do need valid reasons for looking at cultural arguments before they can give them serious consideration. I would suggest that in the case of 1 Timothy 2, there are numerous hints in the text itself that suggest we are wise to look at Paul’s context to better understand his instructions to his protégé.

[1] William Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 994.

[2] Lobe Classical Library (Jones and Ormerod edition) version of Pausanias’s Description of Greece, Vol III (Books VI–VIII), Book V, Chapter 12, Section 2 (V. 12.2).

Just casual, light reading this morning. I always learn so much from you. Thanks for taking us back to the TEXT and also remind us of conTEXT.